Monday, November 10th, marks the official beginning of the 30th United Nations (UN) Climate Summit, better known as COP (Conference of the Parties) or COP 30. It is taking place this year in Belém, Brazil. The Parties are the signatories (198 of them) to the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The places I call home, European Union (EU) and the United States (US) encompass about 19% of guilt for annual CO2 emissions (EU c. 6% and US 12.7% respectively).

Ahead of COP30, a dear friend and environmentalist, Sister Bethany Fitzgerald, shared with me an article, Generative AI’s environmental impact, by Adam Zewe, a clear 101-level explainer of AI’s carbon (and broader) footprint. The article highlights that:

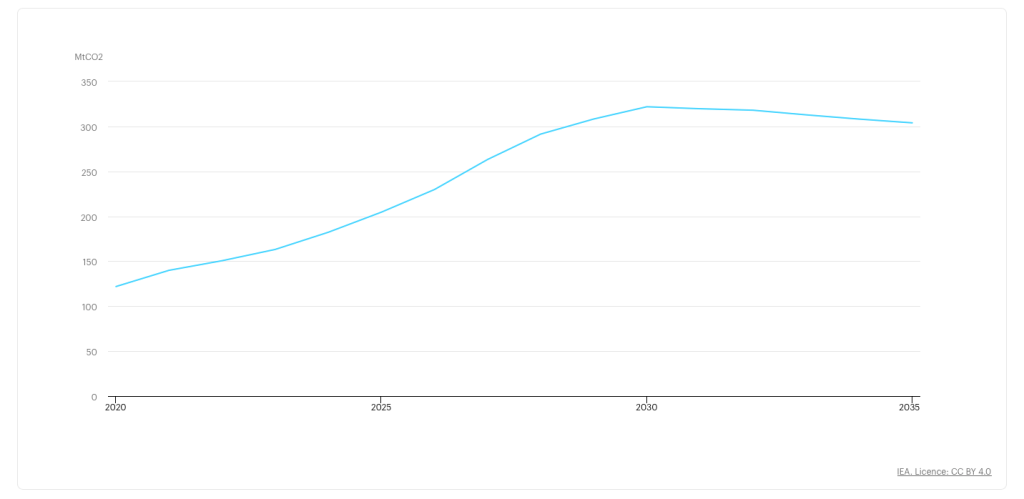

“The power requirements of data centers in North America increased from 2,688 megawatts at the end of 2022 to 5,341 megawatts at the end of 2023, partly driven by the demands of generative AI. Globally, the electricity consumption of data centers rose to 460 terawatt-hours in 2022. This would have made data centers the 11th largest electricity consumer in the world, between the nations of Saudi Arabia (371 terawatt-hours) and France (463 terawatt-hours), according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. By 2026, the electricity consumption of data centers is expected to approach 1,050 terawatt-hours (which would bump data centers up to fifth place on the global list, between Japan and Russia).”

Figure 1: Global data centers CO2 emissions, 2020-2035 (IEA, 2025).

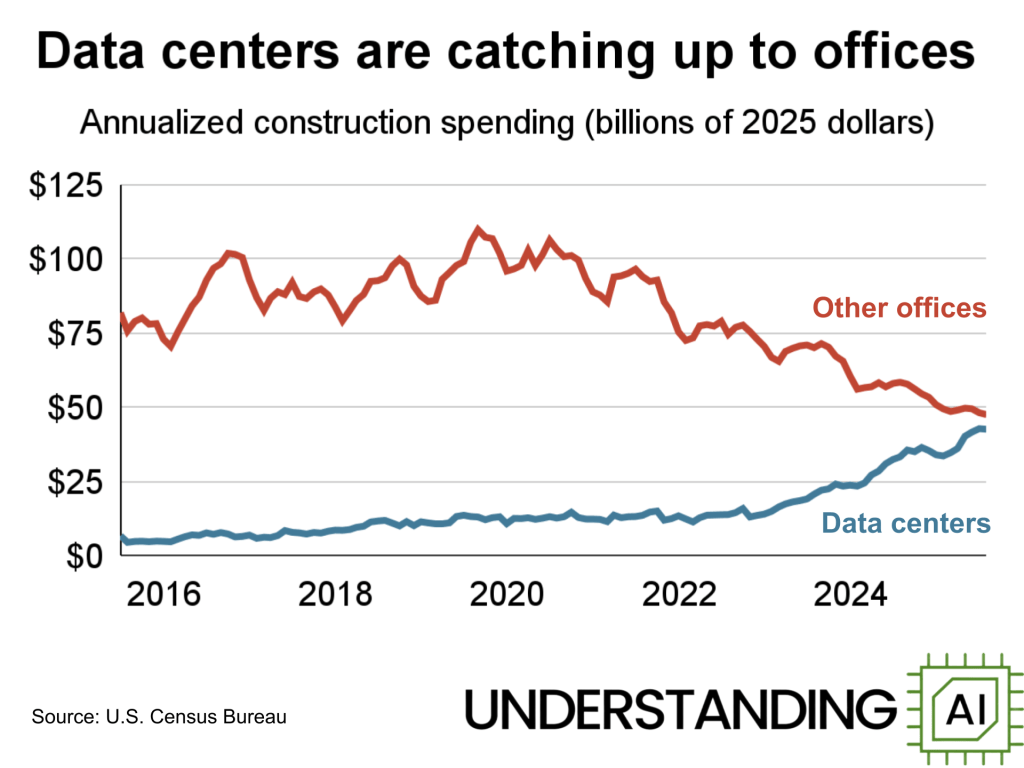

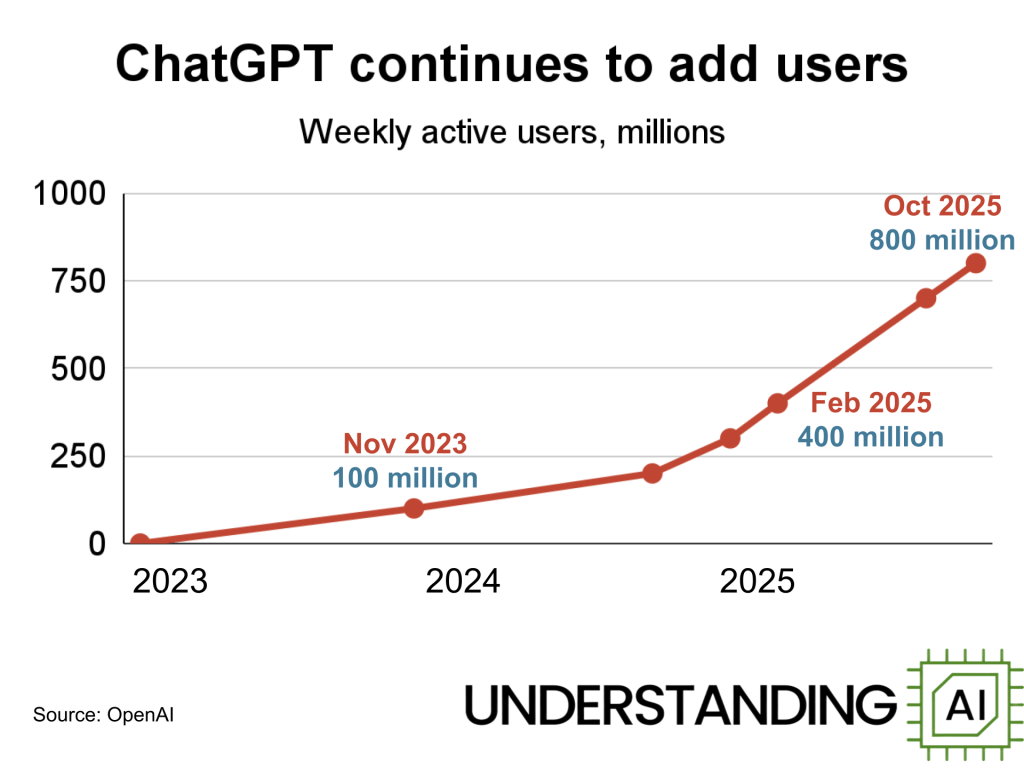

The data centers have been mushrooming around the US as showcased by recent reporting by Kai Williams at Understanding AI. They create significant demands on local communities and the federal government, as their voracious need for electricity and other resources cannot be ignored. As Williams reports, AI adoption continues to accelerate, and many of us, including the author of this piece, contribute to the AI’s footprint whenever we generate images, short videos, run spell checks, or produce summaries. In addition, business media bombard us daily with updates on how NVIDIA and its peers are performing, but what is often overlooked is the environmental and human costs: mining raw materials and processing chemicals for chip manufacturing to produce ever-more GPUs may entail significant harms, as reported by US Environmental Protection Agency and Amnesty International).

Figures 2-3: Data Centers construction 2016-2025 (2) and ChatGPT user-ship 2023-2025 (3) as reported by Understanding AI.*

Upon arrival at COP30, the EU has been flexing its muscles as the climate champion. But once the surface of its old rhetoric is scraped, an enormous challenge appears. The bloc of 27 countries hopes to catch up with the AI sprint of the US and China, while it does not want to relinquish its pole position in the green marathon, creating a seemingly mutually exclusive challenge. Earlier this year, on July 16, 2025, after months of negotiations, Ursula von der Leyen’s Commission published its long-term budget, the Multiannual Financial Framework for the years 2028–2034, intended to make the EU more economically competitive and resilient amidst the ongoing digital (r)evolution. The package amounts to approximately USD 2.31 trillion. But behind the numbers alone, the specter of Mario Draghi’s predictions for EU economy is haunting the EU. Draghi forecasted that without a productivity jump, Europe will be forced to scale back its leadership in technology, climate, and strategic autonomy. That scaling back is compounded by a shrinking workforce, an aging population, and rising energy costs, as Draghi foresees the “agonizing” decline of Europe if action is not taken to close the innovation gap. The winds of change fill the rooms in Brussels and many capital cities, as showcased by The Guardian’s coverage, with some now pushing for deregulation of championed data privacy solutions such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which has become the cornerstone of the so-called Brussels Effect, or pushing to scrap the environmental agenda, leaving eurocrats to run this marathon with rhetoric rather than a genuine commitment to winning. The European Commissions touts plans, for example to exempt around 10 000 companies, in 2026 alone, from fluorinated greenhouse-gas registration requirements and to simplify GDPR record-keeping obligations.

During the summer, on July 23rd, the Trump administration unveiled America’s AI Action Plan, nomen omen called “Winning the Race.” As the US aims to lead technological progress ahead of China, the EU seeks to catch up with both global powers. Each faces unprecedented challenges brought on by the rapid advancement of AI and the inflation of its investment bubble. Their strategies for achieving comparative advantage are strikingly similar, as both must confront a foundational question: How do we literally power the data centers?

In this respect, the US holds both a strategic and ideological advantage. Strategically, it benefits from abundant natural resources it can harness. Ideologically, despite Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” stance on fossil fuels and his administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on June 1, 2017, which took effect on November 4, 2020, his position remains consistent and clear. He was never interested in joining this green rally. The EU, which has spent the past decade positioning itself as a green-norms entrepreneur, now faces the challenge of explaining to its constituents (and other parties) why this policy may no longer be sufficient.

The pressing issue remains, not so much how the EU will finance its data centers and AI factories, which they proudly announced in April of 2025, but rather how it will power them. The AI Continent Action Plan aiming to mobilize €200 billion for AI, up to €20 billion to finance as many as five AI gigafactories, and 19 AI factories. For years, Eurocrats have advanced a green agenda of decarbonization, with some countries, such as Germany, even phasing out nuclear power. This rhetoric has shifted since Russia’s war in Ukraine. Nota bene, unlike other major players, Russia seems too preoccupied with war to worry about how its society can transform with AI and digital technologies. Nonetheless, because the EU borders Russia and has paid the price for a shortsighted embrace of Russian fossil fuels, the EU now finds itself late to the AI sprint and increasingly sluggish in the green marathon. The EU’s paradigm shift is driven by the need to compete in a world undergoing rapid digital transformation, a race the EU is not yet prepared for at least from an energy perspective. As McKinsey estimates, within “the EU, Norway, Switzerland and Britain, the total IT load demand for data centers in the region is expected to grow to around 35 gigawatts (GW) by 2030 from 10 GW today.”

The regulatory strength the EU was once famous for is clearly not sufficient to solve this urgent problem on its own. Every winter, the EU already holds its breath, unsure whether it will have enough energy to heat households (yet another reason why many EU countries such as France, Belgium, Spain and others continue to buy Russian fossil fuels, as Reuters reports). And, if you cannot breathe properly, you are unlikely to run fast enough whether it is a sprint or a marathon. For this reason, COP30 presents a chance to identify new front-runners (Canada? Someone else?), especially since pressing global challenges from climate change require us to run even faster.

*Nota Bene: It is interesting to observe less money being spent on office construction, a trend caused not only by the rise of hybrid and remote work but also by the increasingly salient reduction in demand for office workers, some of which may be offset by AI. Real estate data show that “office conversions and demolitions will exceed new construction in 2025,” and in the International Monetary Fund’s Managing Director, Kristalina Georgieva’s outlook, it is estimated that “in advanced economies, about 60 percent of jobs may be impacted by AI.”

Works Cited:

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, May 9, 1992, S. Treaty Doc. No. 102-38, 1771 U.N.T.S. 107 (entered into force Mar. 21, 1994)

CBRE. (2025, June 2). Office conversions and demolitions will exceed new construction in 2025 for the first time in several years, aiding the office market recovery. https://www.cbre.com/press-releases/office-conversions-and-demolitions-will-exceed-new-construction-in-2025

COP30 Brasil Amazônia—English. (n.d.). https://cop30.br/en

Democratic Republic of Congo: “This is what we die for”: Human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo power the global trade in cobalt. (2016, January 19). Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr62/3183/2016/en/

EDGAR – Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. 2024. European Commission. https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/report_2024

EU budget 2028-2034. (n.d.). https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/eu-budget/long-term-eu-budget/eu-budget-2028-2034_en

European Commission. (2025, April 9). Shaping Europe’s leadership in artificial intelligence with the AI continent action plan. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/ai-continent_en

European Commission. (2025). The future of European competitiveness: Part A—A competitiveness strategy for Europe. Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication. (2025, May 21). Simplification measures to save EU businesses €400 million annually. https://commission.europa.eu/news-and-media/news/simplification-measures-save-eu-businesses-eu400-million-annually-2025-05-21_en

European Commission, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology. (2025, October 30). AI factories. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/ai-factories

Georgieva, K. (2024, January 14). AI will transform the global economy. Let’s make sure it benefits humanity. IMFBlog. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/01/14/ai-will-transform-the-global-economy-lets-make-sure-it-benefits-humanity

Granskog, A., Hernandez Diaz, D., Noffsinger, J., Moavero Milanesi, L., & Sachdeva, P. (2024, October 24). The role of power in unlocking the European AI revolution. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/electric-power-and-natural-gas/our-insights/the-role-of-power-in-unlocking-the-european-ai-revolution

IEA (2025), Global data centre CO2 emissions, Base Case, 2020-2035, IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-data-centre-co2-emissions-base-case-2020-2035

Niranjan, A. (2025, June 26). EU rollback on environmental policy is gaining momentum, warn campaigners. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/jun/26/eu-rollback-on-environmental-policy-deregulation-european-green-deal

Reuters. (2025, September 19). Russia’s LNG exports by destinations and volumes. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russias-lng-exports-by-destinations-volumes-2025-09-19/

The White House. (2025, July). Winning the race: America’s AI action plan. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AI-Action-Plan.pdf

United States – Countries & Regions. (n.d.). IEA. https://www.iea.org/countries/united-states

US EPA (2023, September 15). Semiconductor Industry [Overviews and Factsheets]. https://www.epa.gov/eps-partnership/semiconductor-industry

Williams, K. (2023, July 27). 16 charts that explain the AI boom. https://www.understandingai.org/p/16-charts-that-explain-the-ai-boom?open=false

Zewe, A. (2025, January 17). Explained: Generative AI’s environmental impact. MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. https://news.mit.edu/2025/explained-generative-ai-environmental-impact-0117