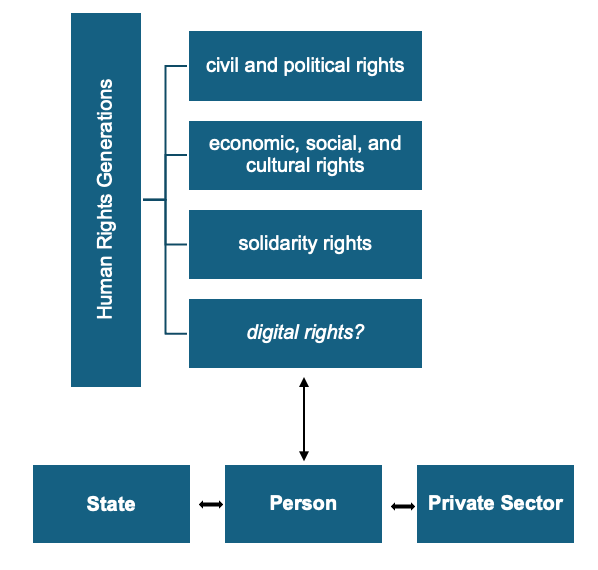

The 4GHR in the emergent typology of human rights law builds from the previous three generations of rights: 1). civil and political rights (e.g., a right to free speech), 2). economic, social, and cultural rights (e.g., a right to shelter), and 3). solidarity rights (e.g., a right to a clean and healthy environment) (Domaradzki et al., 2019; Pedersen, 2017). Do we need a new set of rules to guide humanity forward? Or is what we have so far enough? After all, the vastness of international law, in many instances, is not enforced or obeyed.

There is an unintended possibility that unmitigated digital revolution will cause severe harm that will ultimately require the international community to bend together, just as in the aftermath of the Second World War with the advent of the visionary Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and later legally binding International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). The creation of the international human rights regime under the auspices of Eleanor Roosevelt and other upstanders was reactionary (Glendon, 2002)—like with the drafting of the Genocide Convention thanks to the leadership of Rafael Lemkin (1947); or with the intent to progress society and people forward with the ICESCR by ensuring human dignity and access to public goods. However, are we time and again ‘doomed’ to wait for another catastrophe to arrive so we can be shaken and outline new rules that can govern betterment (would we even be given a second chance this time)? Acting proactively on the digital r(evolution) seems yet to come with stupor and reluctance—despite growing support for regulation as showcased by collected in my research projects data—historically speaking, we are most mobilized when things are already falling on our heads.

The 4GHR needs to encompass a new level of responsibility—the corporate world. The big tech industry, being more prominent than some of the countries out there, cannot remain out of the human rights equation, where, for now, the line of dependency has been drawn between a state and a person. The corporate world needs vested rights and obligations to become part of the human rights metric to deliver on the digital public sphere and other digital public goods. The current equation, where ‘everything’ in the roam of civil and political rights as well as economic, social, and cultural rights take their place between a person (beholder of rights) and a state, the guarantor of rights and deliver of public goods—such schema does not sufficiently reflect the power that consciously or not we have given into big tech. Since breaking them into Exxon and Chevron is unlikely at this point in history, as anti-trust and monopoly rights (or rather those who are supposed to execute them) seem to lag and fall on delivery, the other solution is to see tech giants as agents who deserve adequate recognition, immunity but also when necessary will be held accountable on not delivering on either positive or negative rights—e.g., when they will have to proactively refrain from silencing our freedom of speech or when they will need to deliver the digital public sphere so our expression can take place over there.

Ultimately, this law would bestow the possibility of transforming the tenant into a citizen, or rather a netizen, by enshrining the notion of digital self-determination. Netizens can be defined as “those who use the Internet regularly and effectively […] Digital citizens are those who use technology frequently, who use technology for political information to fulfill their civic duty, and who use technology at work for economic gain” (Mossberger et al., 2007).

Fig. 1. Human Rights Generations and Proposed Relationship between Individual Person, State and Corporate World for the 4GHR

4GHR can provide safeguards and measures to ensure that the least will be harmed when the most might not be needed for labor or generating corporate and other profits. On the other hand, it would not be that far from unimaginable to think about the time in the future when the reverse may happen. The very artificial general intelligence and artificial superintelligence, which we fear today—may also need protection from Homo sapiens as we may treat the ‘AIs’ as less—sentient, smarter, and more efficient, but ‘artificial’ and hence unworthy of equal rights and protections. Thus, to some extent, the 4GHR needs also to encompass the moment when Homo sapiens is not the only sentient being on the planet and perhaps consider the protection over another sentient being, the AI.

More…

As we speak about the 4GHR, it is vital to keep in mind that all human rights are universal, inalienable, indivisible, interdependent, and interrelated (Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, 1993, Part I, Paragraph 5), yet due to political reasons, human rights became ‘clustered’ and ‘contested’, especially during the Cold War Era. The UDHR adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10th, 1948, at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, France, had (and still has) only a political character rather than a legally binding force. At that time, the international community succumbed to the Cold War that cleaved our planet for capitalistic democracies and socialist or communist authoritarian and totalitarian regimes (or other arrangements between each), some exemplifying forms of social democracy, but in general rather following the Leninist principle of the communist party as its vanguard (McAdams, 2019). Some also attempted to remain unaligned. In that reality, when the need for legally enshrining human rights arose, politically divided state parties sought a solution by splitting universal rights (nomen omen indivisible ones) into civil and political rights and economic, social, and cultural rights. Hence, the first and second human rights generations were born. Later, these were followed by the solidarity rights (third generation) (Risse, 2021).

What is more, in the field of digital ethics and human rights, integrating perspectives from the Global South is essential. The Ubuntu‘s philosophy, for instance, offers valuable insights for developing 4GHR. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie cautions against the “single story” narrative (2009), and I am committed to recognizing the Global South as a source of solutions rather than a passive subject. Just as the African continent led the way in articulating the third generation of human rights through the Banjul Charter, it may (and should) also shape the development of the 4GHR.